What the $#@! is parallelism, anyhow?

2022 May 20 — By Charles Leiserson

We take inspiration from Amdahl's Law to give a more "authoritative" introduction to the basic concepts of multithreaded execution — work, span, and parallelism.

parallelismworkspanmultithreadingI’m constantly amazed how many seemingly well-educated computer technologists bandy about the word parallelism without really knowing what they’re talking about. I can’t tell you how many articles and books I’ve read on parallel computing that use the term over and over without ever defining it. Many of these “authoritative” sources cite Amdahl’s Law1, originally proffered by Gene Amdahl in 1967, but they seem blissfully unaware of the more general and precise quantification of parallelism provided by theoretical computer science. Since the theory really isn’t all that hard, it’s curious that it isn’t better known. Maybe it needs a better name — “Law” sounds so authoritative. In this blog, I’ll give a brief introduction to this theory, which incidentally provides a foundation for the efficiency of the OpenCilk runtime system.

Amdahl’s Law

First, let’s look at Amdahl’s Law and see what it says and what it doesn’t

say. Amdahl made what amounts to the following observation. Suppose that

This argument was used in the 1970’s and 1980’s to argue that parallel computing, which was in its infancy back then, was a bad idea — the implication being that most applications have long, inherently serial subcomputations that limit speedup. We now know from numerous examples that there are plenty of applications that can be effectively sped up by parallel computers, but Amdahl’s Law doesn’t really help in understanding how much speedup you can expect from your application. After all, few applications can be decomposed so simply into just a serial part and a parallel part. Theory to the rescue!

A model for multithreaded execution

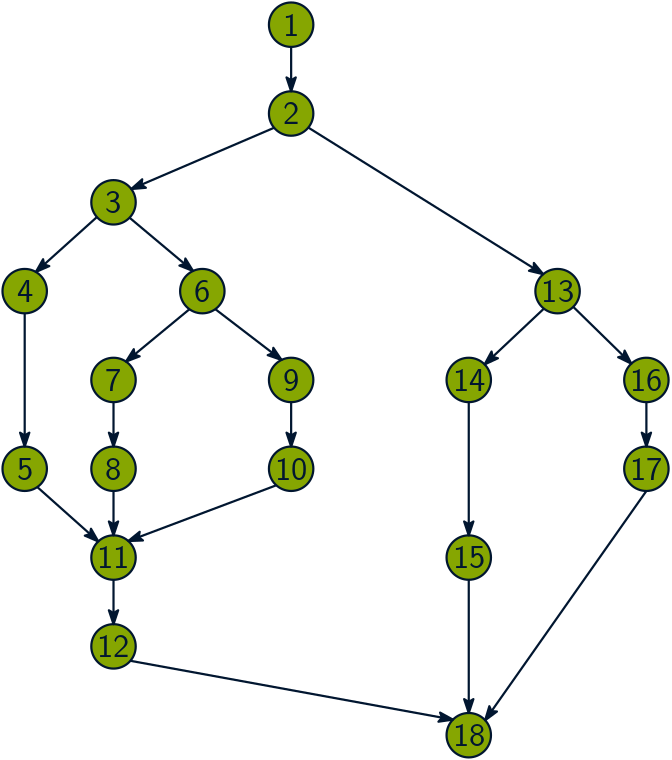

As with much of theoretical computer science, we need a model of multithreaded

execution in order to give a precise definition of parallelism. We can use the

dag model for multithreading, which I talked about in my blog, “Are

determinacy-race bugs lurking in your multicore application? (A dag is a

directed acyclic graph.)

The dag model views the execution of a multithreaded

program as a set of instructions (the vertices of the dag) with graph edges

indicating dependencies between instructions. We say that an instruction

As with much of theoretical computer science, we need a model of multithreaded

execution in order to give a precise definition of parallelism. We can use the

dag model for multithreading, which I talked about in my blog, “Are

determinacy-race bugs lurking in your multicore application? (A dag is a

directed acyclic graph.)

The dag model views the execution of a multithreaded

program as a set of instructions (the vertices of the dag) with graph edges

indicating dependencies between instructions. We say that an instruction

Just by eyeballing, what would you guess is the parallelism of the dag? About

Work

The first important measure is work, which is what you get when you add up

the total amount of time for all the instructions. Assuming for simplicity that

it takes unit time to execute an instruction, the work for the example dag is

Let’s adopt a simple notation. Let

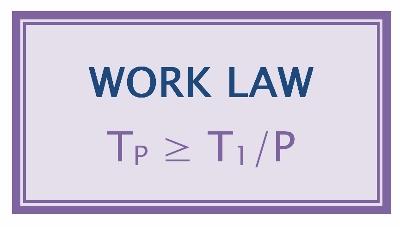

The Work Law holds, because in our model, each processor executes at most

We can interpret the Work Law in terms of speedup. Using our notation, the

speedup on

Span

The second important measure is span, which is the longest path of

dependencies in the dag. The span of the dag in the figure is

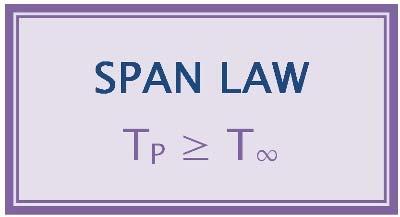

Like work, span also provides a bou…, uhhh, Law on

The Span Law holds for the simple reason that a finite number of processors

cannot outperform an infinite number of processors, because the

infinite-processor machine could just ignore all but

Parallelism

Parallelism is defined as the ratio of work to span, or

- The parallelism

is the average amount of work along each step of the critical path. - The parallelism

is the maximum possible speedup that can be obtained by any number of processors. - Perfect linear speedup cannot be obtained for any number of processors

greater than the parallelism

. To see this third point, suppose that , in which case the Span Law implies that the speedup satisfies . Since the speedup is strictly less than , it cannot be perfect linear speedup. Note also that if , then — the more processors you have beyond the parallelism, the less “perfect” the speedup.

For our example, the parallelism is

Amdahl’s Law Redux

Amdahl’s Law for the case where a fraction

In particular, the theory of work and span has led to an excellent understanding of multithreaded scheduling, at least for those who know the theory. As it turns out, scheduling a multithreaded computation to achieve optimal performance is NP-complete, which in lay terms means that it is computationally intractable. Nevertheless, practical scheduling algorithms exist based on work and span that can schedule any multithreaded computation near optimally. The OpenCilk runtime system contains such a near-optimal scheduler. I’ll talk about multithreaded scheduling in another blog, where I’ll show how the Work and Span Laws really come into play.

1Amdahl, Gene. The validity of the single processor approach to achieving large-scale computing capabilities. Proceedings of the AFIPS Spring Joint Computer Conference. April 1967, pp. 483-485.