The FastCode Programming Challenge aims to push participants to optimize multicore code for high-performance computing applications. Participants will solve two fundamental problems—Breadth-First Search (BFS) and Single Source Shortest Path (SSSP)—designed to test skills in developing efficient, cache-friendly, and scalable algorithms.

This competition emphasizes software performance engineering on multicore architectures. Participants will leverage parallel computing techniques, and scoring will be based on processing efficiency, measured by the speed (edges processed per second) across diverse graph datasets. Competitors will need to refine their solutions for both high- and low-diameter graphs, carefully balancing memory access patterns, load distribution, and scalability to achieve peak performance.

You can submit your solutions on speedcode using the links below:

After you login to speedcode you may be redirected to the home page, if you follow the link again you should be taken directly to the problem page.

You can find instructions to use speedcode here.

Time & Location

- Competition: November 2024 - February 2025, online at speedcode.org

- Workshop: March 2, 2025, at The Westin Las Vegas Hotel & Spa, Las Vegas, NV, USA (affiliated with PPoPP’25)

Problem Descriptions

Problem 1: Breadth-First Search (BFS)

- Objective: Given a graph, perform a BFS traversal starting from a specified source node and compute the shortest (unweighted) distance from the source to each reachable node.

- Input Format:

- Graph Representation: The graph is provided in Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) format, a compact representation that stores edge data efficiently in memory.

- Source Node: A single integer representing the starting node for BFS traversal.

- Distance Array: An array of integers, initialized to

MAX_DISTANCE for all nodes. This array will be updated to store the shortest path (in terms of the number of edges) from the source node to each other node.

- Expected Output:

- The modified distance array with the shortest path lengths from the source node to each reachable node, in terms of edge count. Unreachable nodes should retain the initial

MAX_DISTANCE value.

Problem 2: Single Source Shortest Path (SSSP)

- Objective: Compute the shortest path distances from a given source node to all other nodes in a graph with weighted edges (floats).

- Input Format:

- Graph Representation: As with BFS, the graph will be in CSR format, but with an additional array to store edge weights.

- Source Node: A single integer representing the starting node.

- Distance Array: Similar to BFS, the distance array is initialized to

MAX_DISTANCE for all nodes. Participants should update this array to store the minimum distance from the source node to each other node based on edge weights.

- Expected Output:

- The modified distance array where each element represents the shortest path distance from the source to that node, using edge weights. Unreachable nodes should retain

MAX_DISTANCE.

Dataset Diversity

- Datasets will be selected from a variety of domains and structures to test robustness and adaptability of the solutions. These datasets may vary in the following ways:

- Domains: Social networks, web graphs, computational biology, road networks, k-nearest neighbors (KNN) graphs as well as some synthetic graphs.

- Graph Characteristics:

- Variations in diameter, including small- and large-diameter graphs.

- Diverse weight distributions and ranges for the weighted graphs in SSSP.

Evaluation and Scoring

- Primary Scoring Metric:

- Edges Processed per Second: The primary score will be calculated as the geometric mean of the number of edges processed per second across all datasets. This metric ensures that solutions are evaluated fairly across graphs of varying sizes, densities, and diameters. The top three teams will be awarded first, second and third prizes.

- Bonus Awards for Specialized Excellence:

- Honrable Mentions will be awarded to participants who demonstrate exceptional performance on specific categories:

- Low-Diameter Graphs: Top scores on datasets with low diameters.

- High-Diameter Graphs: Top scores on datasets with high diameters.

- These bonus awards are intended to recognize outstanding optimizations targeted to specific graph characteristics, encouraging innovative approaches for various scenarios within software performance engineering.

Infrastructure and Code Requirements

Programming Language

- All submissions must be written in C++.

Execution Environment

- Platform: The competition will be run on the Speedcode platform, which provides a standardized environment for evaluating and benchmarking submissions.

- CPU Cores: 24 cores available for parallel execution.

- Memory: 96 GB of RAM.

- More details available here

- Parallelization: Participants may use Cilk or OpenMP for parallelization. Solutions are encouraged to leverage parallel computing techniques where appropriate to optimize performance.

- Solutions must operate fully in memory, with no disk or external memory usage during execution.

- A small amount of time is given in the graph constructor for preprocessing.

- This is not counted in the time and can be used to do things like change how the graph is stored.

- The time is roughly equivalent to how long it takes to solve a single shortest-path query sequentially.

Allowed Libraries

- Standard Library: The standard template library is permitted.

- Additional Libraries:

- ParlayLib: ParlayLib on GitHub – A library designed for parallel algorithms and data structures.

- Abseil (absl): Abseil on GitHub – Provides common utilities such as containers, algorithms, and synchronization primitives.

- Additional Library Requests: Participants may request approval to use other libraries, which will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Additional Rules

- Submission Requirements:To be considered as an award winner, the participant(s) are required to submit a workshop paper (described below) and open-source their code.

- Team Structure: Participants can compete in teams of at most two people. There can be more authors in the workshop paper (e.g., including faculty members who help with paper writing).

- No Cached Data: No data can be stored outside the constructor to be used in later computations.

Problem Background

Parallel Breadth-First Search

Background

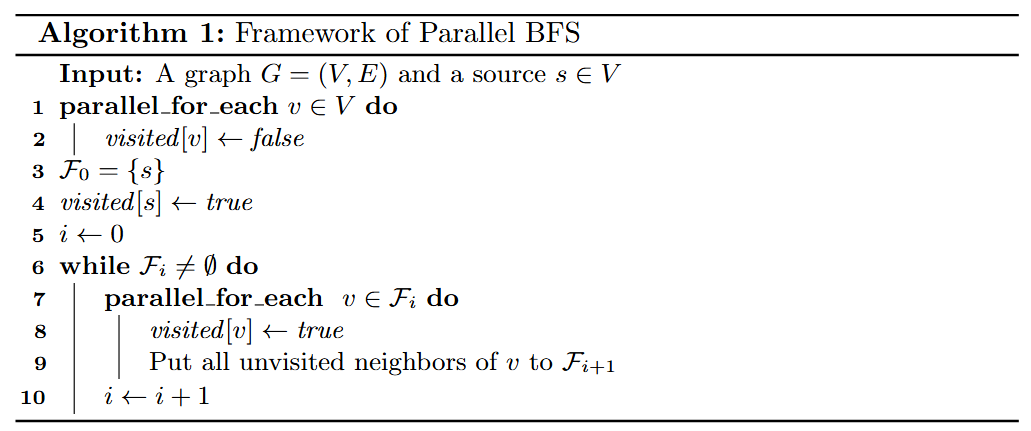

Most of the state-of-the-art parallel BFS implementations are under a frontier-based framework. Starting from a source , the algorithm will visit all the 1-hop neighbors of s in parallel, storing them in the first frontier . In the subsequent rounds, we will always visit all vertices in the current frontier , and generate the next frontier by finding all unvisited neighbors for all vertices in the current frontier . This process is repeated until all vertices have been visited. A simple pseudocode is shown below:

In this case, all the -hop neighbors of s will be visited in parallel in round . The rounds are performed one after the other.

To update the visited array while avoiding duplicates, an atomic operation compare_and_swap is usually used.

Challenges

One inherent challenge in parallel BFS is to achieve parallelism on large-diameter graphs. The frontier-based framework will proceed in rounds, where is the farthest hop distance from any vertex to the source (or roughly, the diameter of the graph). On very sparse graphs with large diameters, the number of rounds can be large, and between them, a global synchronization for all threads is needed.

Some theoretical results focus on using shortcuts or hopset-based ideas to achieve provable low span, but this usually increases work and it remains unknown whether they can be practical.

Existing Optimizations

We overview two existing optimizations here. The contestants may choose to use them to improve their performance (references are provided). We also look forward to novel ideas provided by the contestants to address the aforementioned challenges!

A common optimization for parallel BFS is called directional optimization [1]. When the frontier size is large, instead of generating the next frontier from the current frontier, one can simply process all vertices in parallel, and determine if one of their in-neighbors is in the current frontier. If so, they are added to the next frontier, and all the rest of the neighbors can be skipped. Such a “pull” version of frontier generation may allow for better cache locality, as well as a simpler frontier representation using just bit-flags. On dense graphs such as social networks, existing results show that this optimization is very effective in improving performance by saving work - the running time of the parallel algorithm on one core can be faster than the standard queue-based sequential solution.

A recently developed optimization to address the low parallelism on large-diameter graphs is vertical granularity control [2]. The high-level idea is to explore multiple hops in one round, so that it makes much fewer rounds to finish BFS. The approach allocates a small “buffer” of size for each visited vertex in the frontier in the stack memory (invisible from other processors), and does a mini-BFS in the buffer. Once sufficient work is done (either visiting a fixed number of vertices or edges), the rest of the vertices will be flushed to the next frontier. Note that in this implementation, a vertex might be visited multiple times, so this technique is inherently a work-parallelism trade-off.

Parallel Single-Source Shortest Paths (SSSP)

BFS can compute unweighted SSSP. The general SSSP on weighted graphs is strictly harder. Sequentially, the classic solutions include Dijkstra’s algorithm, Bellman-Ford, and more. In most real-world instances, Dijkstra is usually the most efficient. However, Dijkstra visits one vertex at a time, which is inherently sequential.

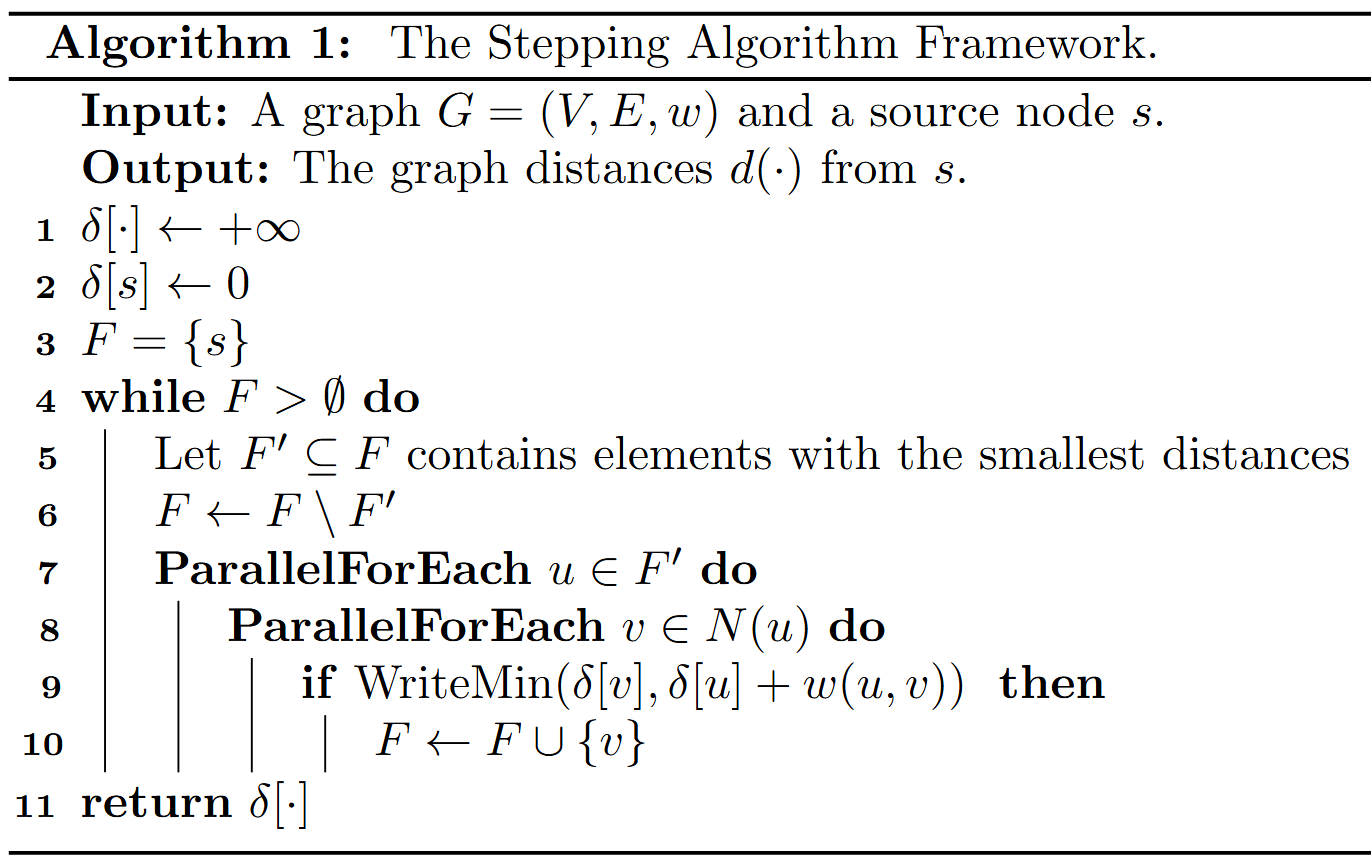

There exist parallel SSSP algorithms, which are generally referred to as stepping algorithms [3] as shown below. They also keep a frontier of “active” vertices, denoted as , like in BFS, Dijkstra, and Bellman-Ford. The high-level idea of this framework is that in each round, the algorithm extracts a subset of vertices from with the smallest distances, as they are likely to be close to the final distances, and less likely to be frequently updated by other vertices. For example, in -stepping [5], in the -th round, all vertices with distances no more than will be extracted. In -stepping [3], in each round, the vertices in with the smallest distances will be extracted.

Challenges and existing optimizations:

Similar to BFS, the performance of parallel SSSP is limited on large-diameter graphs, due to a few reasons. On large-diameter graphs, the frontier size is smaller, usually given insufficient parallelism. One can probably extract vertices more aggressively (i.e., a larger ), by setting up a larger or , with the goal of improving parallelism. However, this is likely to cause multiple rounds of revisiting to the same vertex, which will lead to significant extra work. An existing attempt to resolve this issue is also the vertical granularity control (VGC) [3]. It allows exploration of multiple hops from the current frontier in the same round to increase parallelism. However, it will also lead to some extra work.

Another challenge is the parameter choosing: in both -stepping and -stepping, the parameter affects the performance---a larger parameter causes excessive extra work in revisiting the vertices, while a smaller parameter leads to insufficient parallelism. One may want to auto-tune the best parameter. Attempts can be found in some existing papers such as [4].

Preprocessing

Certain preprocessing may improve the performance for both BFS and SSSP. In both problems, we allow for a small amount of preprocessing time. Some possible optimizations you can consider include:

- Finding the best parameters of the algorithm (use simple preprocessing to decide the best parameters, such as Delta in Delta-stepping)

- Graph reordering (changing the ordering of vertices to achieve better cache locality

- Shortcuts (adding shortcuts to reduce graph diameter)

You can explore more optimizations to enable more effective preprocessing.

Useful References:

[1] “Direction-Optimizing Breadth-First Search” by Scott Beamer, Krste Asanovic, David Patterson

[2] “PASGAL: Parallel And Scalable Graph Algorithm Library” by Xiaojun Dong, Yan Gu, Yihan Sun, and Letong Wang

[3] “Efficient Stepping Algorithms and Implementations for Parallel Shortest Paths” by Xiaojun Dong, Yan Gu, Yihan Sun, and Yunming Zhang

[4] “GraphIt: A High-Performance Graph DSL” by Yunming Zhang, Mengjiao Yang, Riyadh Baghdadi, Shoaib Kamil, Julian Shun, and Saman Amarasinghe

[5] "-stepping: a parallelizable shortest path algorithm." by Ulrich Meyer and Peter Sanders.

Existing open-source parallel implementations for SSSP and BFS:

You can find relevant publications on their websites.

Writting Parallel Code

If you are new to writing parallel codes - no worries. Speedcode supports many libraries that you can directly use to write parallel codes. We will use OpenCilk as an example to give you basic instructions here to use fork-join parallelism.

In general, the only thing you need to consider in addition to writing sequential codes is to specify some parts of your code to run in parallel. As an entry-level attempt, you can just consider two semantics:

cilk_scope/cilk_spawn

A cilk_spawn can be inserted before a function call to allow that call to execute in parallel with its continuation. A cilk_scope defines a lexical scope in which all spawned subcomputations must complete before program execution leaves the scope. An example is shown below:

cilk_scope {

x = cilk_spawn fib(n-1);

y = fib(n-2);

}

return x+y;

The code above will use two threads to work on two tasks x = fib(n-1) and y = fib(n-2) in parallel. When they both finish, the next statement outside cilk_scope will be executed and return x+y.

cilk_for

You can replace for with a cilk_for to enable a parallel for-loop: all loop iterations will be executed in parallel.

Some useful documentations about using OpenCilk are available here:

https://github.com/OpenCilk/opencilk-project?tab=readme-ov-file#a-brief-introduction-to-cilk-programming (by Tao B. Schardl)

https://www.opencilk.org/doc/ (official documents from OpenCilk)

When writing parallel codes, you may need to be careful about concurrent write to the same memory location - in the real execution, the threads are highly asynchronous, and this may cause errors if their relative order to write to the memory location is different. A common way to deal with concurrent writes is to use atomic operations such as compare_and_swap. You can use it to implement a write_min (atomically update the value of a memory location iff the new value is smaller) operation which is useful for both BFS and SSSP.